“Mass incarceration” may be a misnomer

The majority of the US did not experience a drastic rise in imprisonment

America is home to 5% of the world’s population, yet approximately 25% of the those locked up around the globe. There was a 500% increase in our incarceration population since the 1970s, which was largely the result of changes in criminal justice policy (specifically more punitive sentencing policies). These are the common statistics and talking points that get thrown out when discussing the US’ experiment in “mass incarceration.”

America, undoubtedly, has some of the highest rates of incarceration in the world. And the differences are particularly glaring when compared to other, similarly situated countries (e.g., Canada, Australia, Western Europe).

Yet, I’m starting to get a sense that the term “mass incarceration”, which I’ve heard and largely agreed with since my undergraduate days, is a misrepresentation. Mass incarceration does not characterize most of the country; instead, incarceration is extremely concentrated in a small number of economically disadvantaged and racially/residentially segregated places. Those places experienced a disproportionate rise in incarceration over a several-decade-long period. Yet, many Americans are naïve since all of this – the prisons themselves and the neighborhoods they hail from and return to – are divergent social worlds far, far away. Out of sight and out of mind.

This, by the way, is not an original thought. In fact, many scholars way smarter than me have made the point long ago. I am now simply coming across them and their studies since I haven’t paid much attention to corrections and/or offender reentry since comprehensive exams. For example, Robert Sampson and Charles Loeffler stated in 2010, when talking about “hot spots” of incarceration:

“Although the inhabitants of such communities experience incarceration as a disturbingly common occurrence, for most other communities and most other Americans incarceration is quite rare. This spatial inequality in punishment helps explain the widespread invisibility of mass incarceration to the average American.”

Just how concentrated is incarceration and, subsequently, reentry? Let’s take a look at a few places.

The impetus for this post is the fact that I stepped out of my wheelhouse to read a non-policing book. I’m in the process of finishing Reuben Jonathan Miller’s “Halfway home: Race, punishment, and the afterlife of mass incarceration.” It’s been great so far, and I’m really enjoying it.

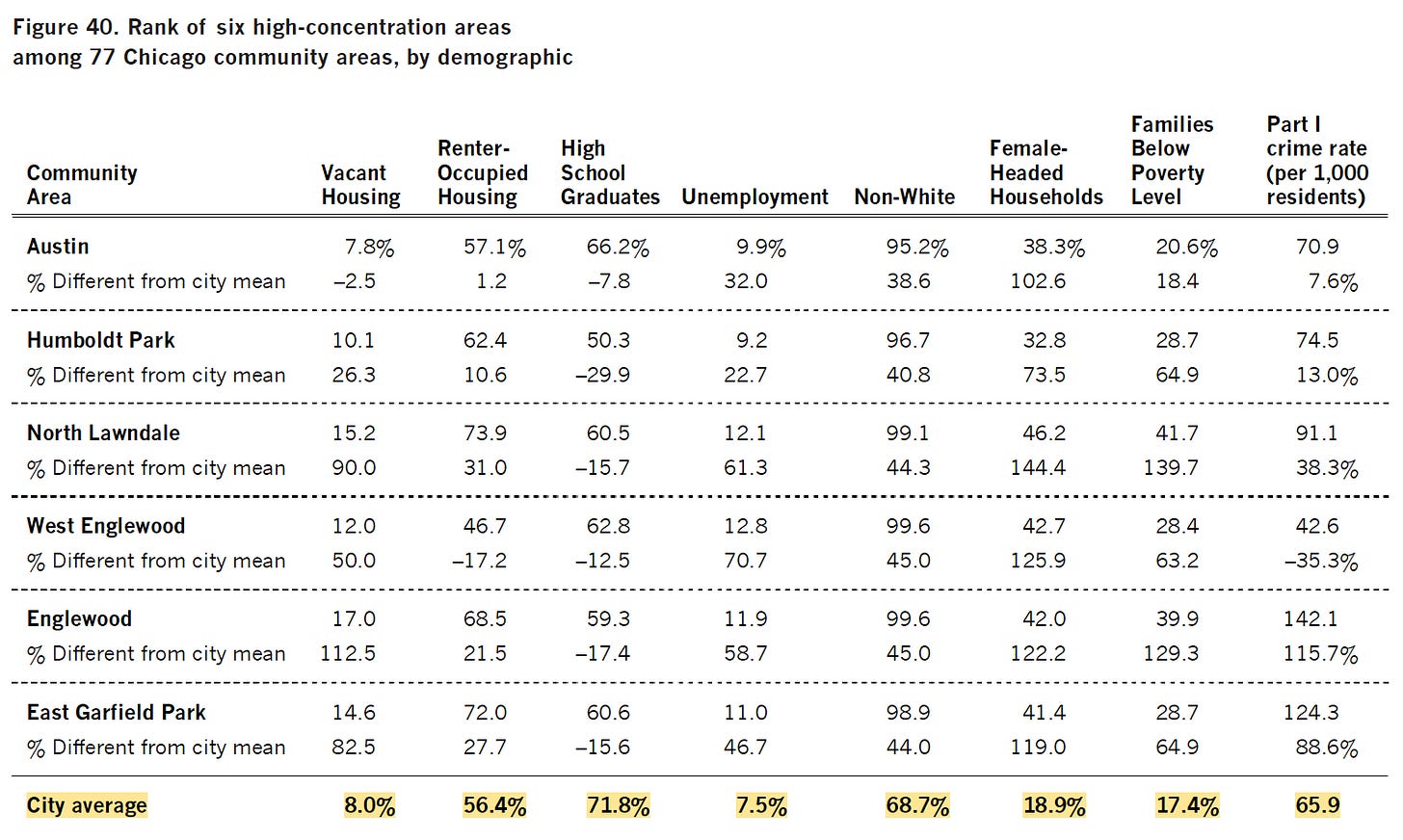

Perhaps one of the most striking ideas that the book addresses is the concentration of incarceration and offender/prisoner reentry. Miller talks about an Urban Institute study from the early 2000s that examined Illinois’ prison population.

1/2 of the state’s prison population comes from Chicago.

Of that 1/2, 1/3rd of Chicago’s prison population comes from just 6 of the city’s 77

neighborhoods: Austin, Humboldt Park, North Lawndale, Englewood, West Englewood, and East Garfield Park.

This means that approximately 17% of the state’s prison population comes from 6 neighborhoods! That’s incredible and tragic at the same time.

Another report from the early 2000s examined the percentage of adults incarcerated or under criminal justice supervision from one of those 6 neighborhoods in North Lawndale. In 2001:

24% of adults had new involvement in the CJ system (i.e., sentenced to prison or probation).

57% of adults were currently in the CJ system: including prison, probation, or parole.

Nearly 70% of men aged 18-54 were currently in the CJ system.

Incarceration and reentry back into the community are incredibly concentrated in neighborhoods, census tracts, and even street segments. The term “million-dollar block” was coined for street segments that cost over $1,000,000 per year to lock up residents from said block. Chicago is notorious for having many million-dollar blocks. In Chicago, over a 5-year period from 2005-2009, there were:

851 blocks with over $1 million committed to prison sentences overall.

121 blocks with over $1 million committed to prison sentences for non-violent drug offenses.

But million-dollar blocks exist in cities across the country. They are usually, again, economically disadvantaged and racially/residentially segregated places. You can check them out here.

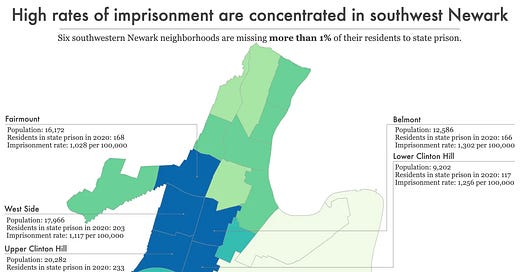

Like most policy-relevant areas, I was curious to see how incarceration clusters in my home state of New Jersey. Luckily, the state abolished prison gerrymandering so the state must count inmates not from where they are currently incarcerated but from the places that they hailed from prior to going to prison. The Prison Policy Initiative and the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice collaborated to provide the county, select municipality, zip code, and census tract breakdown of the where the state’s prison population came from in 2020. You can read about it here and also check out their data. As expected, incarceration is concentrated in New Jersey:

3.5% of municipalities (n = 20) account for approximately 56% of the state prison population. The highest totals come from: Newark (1,957), Camden (1,078), Paterson (1,019), Trenton (812), Jersey City (741), Atlantic City (479), Elizabeth (476), East Orange (405), Plainfield (287), New Brunswick (273) and 10 others.

5% of zip codes (n = 30) account for approximately 47.5% of the state prison population.

3.7% of census tracts (n = 80) account for approximately 25% of the state prison population. In most of these tracts, the rate of incarceration is usually over 1,000 persons per 100K.

Remember from a few posts back that NJ spends $61,603 per prison inmate per year. While we cannot necessarily examine million-dollar blocks with these data, it’s easy to identify million-dollar-census tracts. Any tract that locks up 17 or more people essentially costs over $1 million per year.

It costs the state of NJ approximately $250 million to lock up the 4,052 prison inmates (25% of total) from those 80 census tracts (3.7% of total tracts in NJ).

Perhaps mass incarceration isn’t the right term. Maybe it’s better to use “concentrated mass incarceration” or “stratified mass incarceration.”

John, first, I’ve really been enjoying your posts. Please keep them coming. Second, the term mass incarceration is highly politically charged and often used by progressives of all kinds (academics, activists, politicians) to suggest that the United States (or at least parts of it) locks up people of color at massive rates for no legitimate reason. If you overlaid violent crime data on the same city maps in Chicago and New Jersey, you would see a high degree of spatial correlation with the rates of incarceration driving the Illinois and New Jersey prison populations. And behind each one of those data points was a crime, an investigation, a guilty plea, or a conviction at trial. Perhaps the better term to describe the phenomenon is “concentrated offending,” driven by guns and all of the social ills that continue to plague American cities. High incarceration rates are a sad commentary on American society, but they are not irrational.